Emergency Contact Information Programs Help Save Lives

CARS.COM — When Christine Olson’s daughter, Tiffiany, was involved in a motorcycle crash in 2005, it took Florida law enforcement personnel 6 1/2 hours to locate Olson even though the crash occurred just 15 minutes from her home. By that time, Tiffiany, whose driver’s license had an out-of-date address, was dead.

Related: More Safety News

The national average for next-of-kin notification in emergencies is six hours. Olson’s tragedy, and fatal accidents in other states, gave birth to what has become a movement to create emergency contact information databases accessible only by law enforcement.

Following Tiffiany’s death, Olson began a petition drive to put emergency contact information on Florida driver’s licenses. The petition led to meetings with Florida legislators. They refined Olson’s idea, passed legislation to create an ECI database linked to driver’s licenses, and put the program into practice in 2006.

“I have no background in government, law enforcement or anything like that,” said Olson, who is a server at a Florida restaurant. “What I know was wrong was what happened to me that night.”

Ohio and Illinois enacted similar programs in 2008 and 2009, respectively, and other ECI databases have been rolling out across the country; more than a dozen states now offer voluntary ECI programs.

Olson calls these programs a win-win for everyone: They save time for law enforcement and have the potential to save lives.

The programs work by connecting emergency contact information to driver’s licenses; depending on the state, first responders can scan the license or punch the driver’s license number into a database and retrieve next-of-kin information. Quick access to family members can mean the difference between life and death when an injured person is unable to communicate and his or her cellphone, where many of us store emergency contact information, is locked.

These databases can provide peace of mind for the parents of teen drivers and the adult children of mature drivers, Olson said, and have applications beyond car collisions. They can be used in any kind of emergency for which law enforcement is summoned.

Mary Riseling, an analyst in the Illinois Secretary of State’s programs and policies office, agrees that ECI programs have applications beyond car crashes. The challenge most states face, she said, is promoting the programs and making the public aware of their existence. Three years younger than Florida’s program, where more than 11 million drivers are registered, Illinois’ emergency contact database has just 235,810 drivers enrolled through June 2016. Riseling said she focuses her public education efforts on the two populations with the highest risk of crash fatalities: teen and senior drivers.

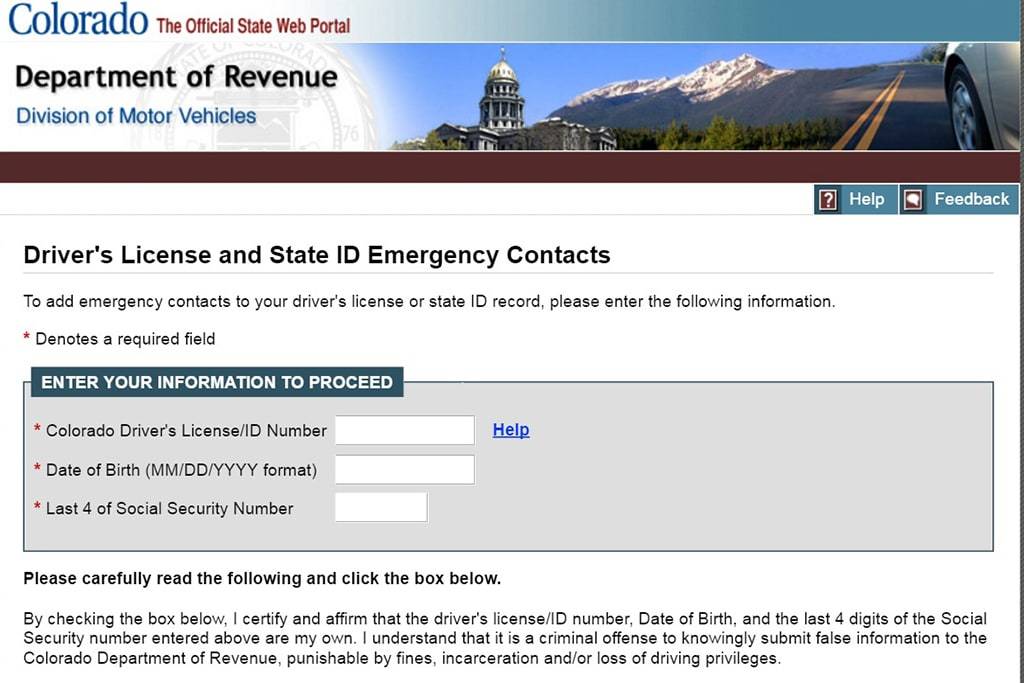

Registration occurs through secretary of state, state motor vehicle and transportation, or state revenue departments. Most states provide online registration; some offer paper or phone registration as alternatives. A few states make emergency contact information an optional part of the driver’s license application. If your state offers only online registration and you don’t have a computer, visit your local library to register. Registration in any form takes just a couple of minutes, and anyone with a driver’s license, learner’s permit or state ID can register one to three (depending on the state) emergency contact numbers and often information about medical conditions. The info can be updated whenever necessary, but each state has different rules about how to do so.

Since ECI program names vary by state and not all state government websites are user-friendly, Olson is working to provide navigation links to state ECI programs through the nonprofit To Inform Families First website. Right now, there are links to five states and she hopes to include more.

Preventing others from experiencing the anguish she did has become Olson’s mission. Her initial goal of registering all Florida drivers has grown to the more ambitious objective of registering drivers across the U.S. and around the world.

“I want to make sure that every person out there, however this travels throughout the United States and beyond, never has to worry,” she said. It’s important to her “that they have a sense of a peace of mind knowing that law enforcement has their contact information” in the event of an emergency.

What can you do if you live in a state without an ECI program? Several states have Yellow Dot programs that link a round yellow sticker placed on the rear window of a vehicle to cards in the glove box; cards with emergency contact and medical info can be filled out for drivers and passengers. When first responders see that yellow dot, they know to search the glove box. Even if your state doesn’t have a program, it’s still helpful to first responders to carry an emergency contact card in your wallet and glove box.

In addition, Olson encourages drivers whose states don’t have ECI databases to visit the TIFF website to sign and send a petition to their state legislators urging them to enact an ECI program.

She also urged drivers whose states do have ECI programs to register and tell others about it.

“It takes everybody taking a moment to register and paying it forward. Let three to five people know,” Olson said. “Take a moment, get this done. Because the worst thing, you know, is you sign up and you don’t tell anybody about it. … It’s so helpful and it’s rewarding, and it’s just good stuff.”

Former Assistant Managing Editor-Production Jen Burklow is a dog lover; she carts her pack of four to canine events in her 2017 Ford Expedition EL.

Featured stories