What Makes Up a Destination Charge?

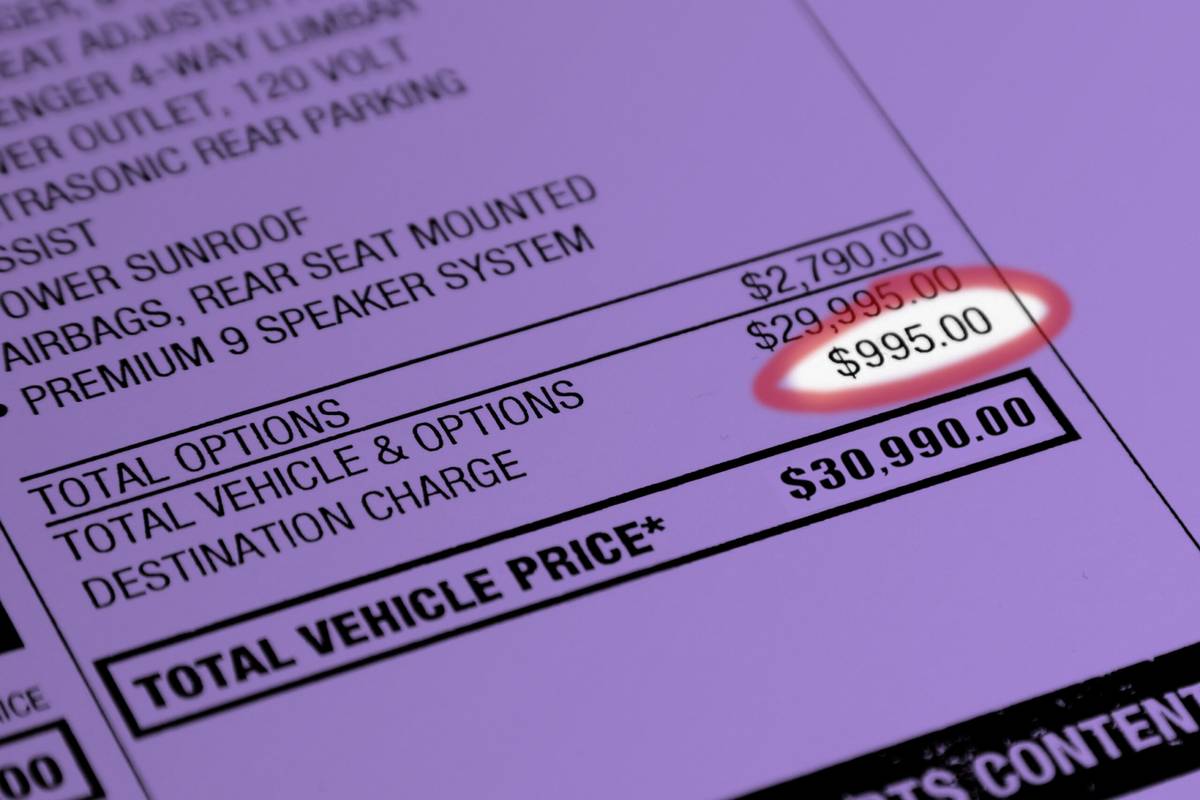

Federal legalese defines the destination charge as a required line on new-car window stickers. It discloses “the amount charged, if any, to such dealer for the transportation of such automobile to the location at which it is delivered to such dealer.” Along with the entries for the vehicle’s base price and extra-cost options, a destination charge is simply part of the bottom-line suggested retail price for the car and is not a separate negotiable fee. It’s generally listed after the base price and options and before the vehicle’s total MSRP, and you’ll pay state sales tax on it.

Related: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About a Dealer Doc Fee

What’s in the Secret Sauce?

As the name implies, the bulk of the destination charge goes for hauling the vehicle from a factory or port to the dealership. What else makes up the charge gets fuzzier from there (and the industry generally is reluctant to comment on it); it also can include some prep and processing services. As with every other line on the sticker, there is surely a little markup for profit in there.

Automakers have various names for the charge, from simply “destination” to “destination and handling,” “destination freight,” and “inland freight and handling.” Toyota lists it more specifically as a “destination, processing and handling fee.” Spokesman Zachary Reed says the amount of the fee “is based on the value of the processing, handling and delivery services Toyota provides as well as Toyota’s overall pricing structure.”

One Size Fits All

One reason the destination fee is hard to pin down is that it’s not the cost to deliver a particular vehicle to a dealer. Automakers calculate a national average and charge the same destination fee for a given vehicle no matter where in the U.S. it is bought or where it is made, putting all buyers and dealers on an equal footing — though fees for Alaska and Hawaii sometimes differ. So, a 2025 Honda CR-V built in Ohio carries the same $1,350 destination fee whether you buy it at a dealer in Cleveland or in Seattle.

Destination charges do vary among individual vehicles, however. The fee for bigger, heavier vehicles is generally more than a regular car’s, as is the fee for luxury vehicles, even if only the price is bigger. Reed says that Toyota calculates the fees for its different vehicles “by vehicle segment” and that the fee “includes many factors, including vehicle weight, size, load factor and point of origin.”

Separate Fee Still Is Odd

Contrary to what many think, automakers are not required to add a separate destination fee. The rule only says they have to disclose a separate amount charged — if any — for delivery to the dealership. But in practice, they all do it, even brands that sell directly and not through franchised dealers.

That’s an unusual practice among even big things you buy, as most products bake such expenses into the retail price. If you buy a refrigerator, for instance, you don’t pay a separate charge for the transportation from the factory to the Home Depot. In fact, some shipping is already baked into the price for many vehicles. The destination charge is for transport in the U.S. from the factory or port, but travel to the port from a foreign plant is baked into the imported car’s base price.

The Fee Is Inflating Faster Than Inflation

Inflation has pumped up the costs for everything in recent years — including the fuel, labor and freight rates — but destination fees have gone up faster than inflation, according to a 2021 study by Consumer Reports. The study’s analysis found that mainstream brands raised fees from an average of $839 in 2011 to $1,244 in 2020, more than two-and-a-half times the rate of inflation over those years.

In one way, that doesn’t matter, since what matters in the end is the total MSRP, not any one line on the sticker, but the destination fee can be used to mislead shoppers because automakers and dealers often advertise the base price in advertising. Then, when shoppers arrive at the dealer, they find the real sticker price is $1,000 to $2,000 higher thanks to the destination fee. Some states require car advertising to show the full price, including all mandatory fees, and Consumer Reports has lobbied for more such regulation. (Prices given in Cars.com’s news and reviews coverage include the required destination charge.)

What’s the Average Destination Fee?

Here is a list of the average destination charges by vehicle type.

- Subcompact car: $1,144

- Compact car: $1,153

- Mid-size car: $1,146

- Small sports car: $1,210

- Compact luxury car: $1,171

- Mid-size luxury car: $1,164

- Full-size luxury car: $1,388

- Luxury sports car: $1,823

- Small pickup truck: $1,557

- Large pickup truck: $2,001

- Subcompact SUV: $1,342

- Compact SUV: $1,447

- Mid-size SUV: $1,495

- Full-size SUV: $1,878

- Compact luxury SUV: $1,272

- Mid-size luxury SUV: $1,478

- Full-size luxury SUV: $1,494

Beyond the averages, there are a couple of individual vehicles that have already broken the $2,000 barrier for destination; Jeep’s 2024 Wagoneer and Grand Wagoneer currently charge an even two grand, while Ford’s 2024 F-150 Lightning electric pickup weighs in at $2,095.

More From Cars.com:

- How to Negotiate With a Dealer

- How to Negotiate a Car Lease

- What Are Dealer Options and Are They Worth It?

- Are Extended Car Warranties Worth It?

- What Does MSRP Mean?

- Sub-$30,000 New Cars Are So Hot Right Now: Report

- How Much Does It Cost to Lease a Car?

- More Car Buying Advice

Related Video:

Cars.com’s Editorial department is your source for automotive news and reviews. In line with Cars.com’s long-standing ethics policy, editors and reviewers don’t accept gifts or free trips from automakers. The Editorial department is independent of Cars.com’s advertising, sales and sponsored content departments.

Former D.C. Bureau Chief Fred Meier, who lives every day with Washington gridlock, has an un-American love of small wagons and hatchbacks.

Featured stories