What to Know Before Buying a Used Electric Car

In many ways, driving an electric vehicle is the same as driving one with an internal-combustion engine, though refueling and other ownership aspects are certainly different, and we’ve recognized that the considerations for buying a used EV are quite different as well. Where a used vehicle has spent its life (geographically speaking) and how it’s been cared for are still primary concerns, but the rules are surprisingly different from — and perhaps the opposite of — those for conventional cars. Pre-owned EVs also put an interesting spin on pricing, warranties and features that you might not give a second thought with a gas-powered car. We explore these issues below.

Related: What to Know Before Purchasing an Electric Vehicle: A Buying Guide

Used EVs Can Be a Bargain

Cars.com purchased its first EV, a 2011 Nissan Leaf SL, new for $35,665 as equipped, and when we sold it 19 months later to a private party with just 11,000 miles on it, $19,000 was the best we could get for it — a depreciation of 47%. More recently, we purchased a 2021 Tesla Model Y for $66,443, which we traded in more than two years later for $26,800. While trade-in value is always going to be slightly less than resale, we still only made back roughly 40% of the Model Y’s initial cost.

There are a few factors that result in modest used-EV prices. One is incentives. The market immediately accounted for federal tax credits available on new EVs, which subtract up to $7,500 from the apparent purchase price of most pre-owned battery-electrics even though not all EVs qualify for them. State and local incentives also play a part in used-EV depreciation depending on where you buy. The revised federal tax credit also introduced used-EV incentives, which can knock up to $4,000 or 30% (whichever is lower) off the purchase price of a used EV for qualifying buyers.

Best we can tell, the rest has been about consumers’ hesitancy to purchase used EVs because they’ve believed a few things: that newer models would be coming with longer ranges, faster charging capabilities and better features (true), that they truly needed more range (often false), and that a used EV is closer to imminent and prohibitively expensive battery death (highly unlikely).

We’ll address the biggest boogeyman next, but suffice it to say that shoppers with the right perspective on these concerns and all the facts below have gotten some great deals on used EVs.

Focus on Decreased Range, Not Battery Death

As we’ve reported many times, electric car batteries are more like those in hybrids than cellular phones: They lose capacity over time, but outright failure requiring replacement is very rare. This should allay one of the primary fears about buying a used EV, but just the same, you should think about what your daily range needs are and make sure you reconcile that not with a brand-new version of the car’s EPA-estimated range, but rather a vehicle of its current age. While you’re at it, allow for further range loss if you plan to keep the vehicle for years to come.

All makes and models age differently, and the way they’re charged and driven affects battery health, as does the climate (more on that below), but based on the data available today, it seems that most EVs lose 10%-20% of their capacity over 10 years. Don’t forget to account for the inevitable temporary range decrease caused by cold temperatures if it applies to you, which is roughly 40% at 20 degrees Fahrenheit compared with the ideal 75 degrees. This is pretty linear, meaning it gets steadily worse on its way down to 20 degrees, and it doesn’t stop there. Subzero temps easily mean half of your range is gone.

Beware the Desert Car?

Having established that outright battery failure is rare, we don’t want to proceed to scare everyone off of used EVs. However, there are some considerations to ponder, and one example in particular resonates because it illustrates how different EVs can be from what we’ve always known: the desert car.

People of a certain age were taught that a used car from a desert climate with low mileage (meaning miles on the odometer) was the best you could hope for. The desert meant it wasn’t exposed to much rain, road salt or sea air, and consequently, it was less likely to rust. Plus, low miles is a good thing for a used car, as that equals higher value. Fast forward and cars are now so rust-resistant that the desert might not be the advantage it once was — but did anyone expect it to become a disadvantage? In the age of EVs, one could argue it is. EVs unavoidably lose range as they age, but the data also show that hot climates accelerate this degradation.

Lower odometer readings are also a plus, all other things being equal, partly because it should reflect that more of both the original battery capacity and the warranty remain. But once again, the data tell us an EV that’s regularly used is a happy EV, while one that’s driven or charged infrequently can incur battery damage, specifically if it’s allowed to discharge too far and for too long, or to sit unused indefinitely at 100% state of charge. How do you know if a used car meets this description? One way is via Recurrent, a company that monitors connected EVs in the U.S. and analyzes the resulting battery data to determine how specific makes and models age. Using basic information, the company believes it can determine the health of an EV battery and has even alerted a couple of its community members, who allow Recurrent to retrieve data wirelessly, of batteries that were failing prematurely due to manufacturing defects.

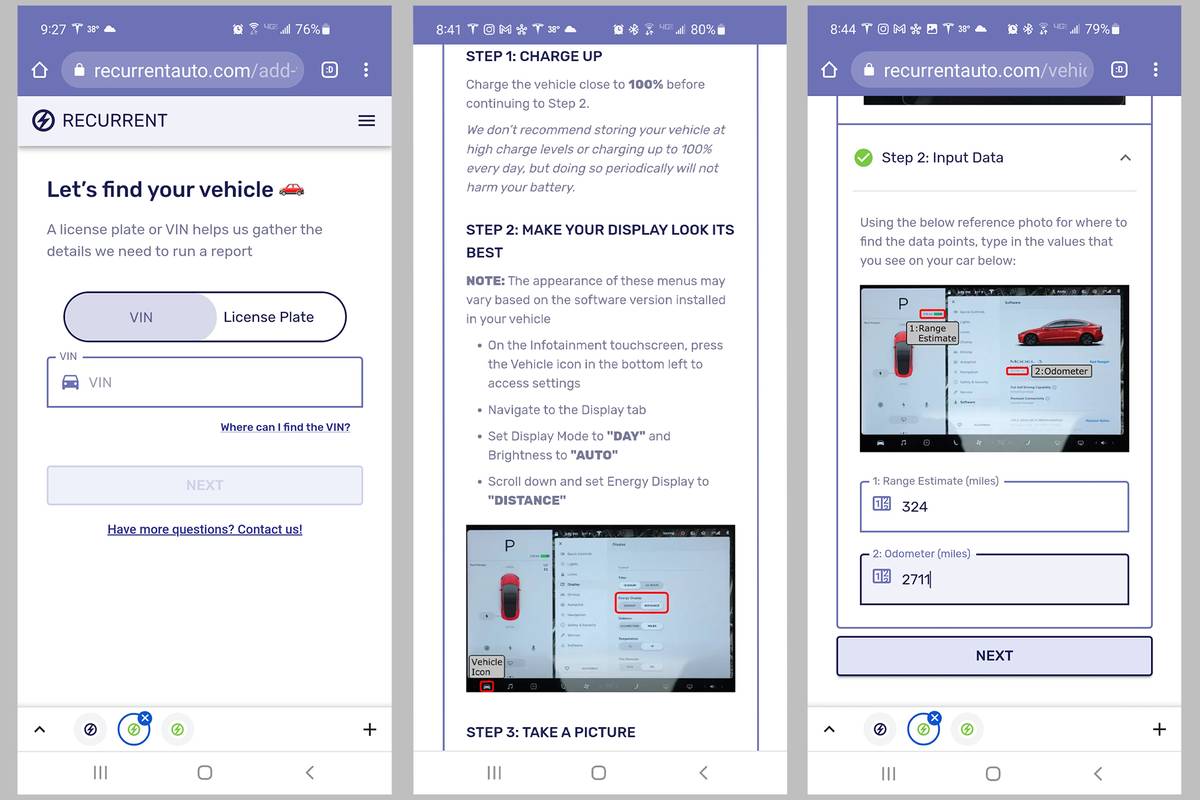

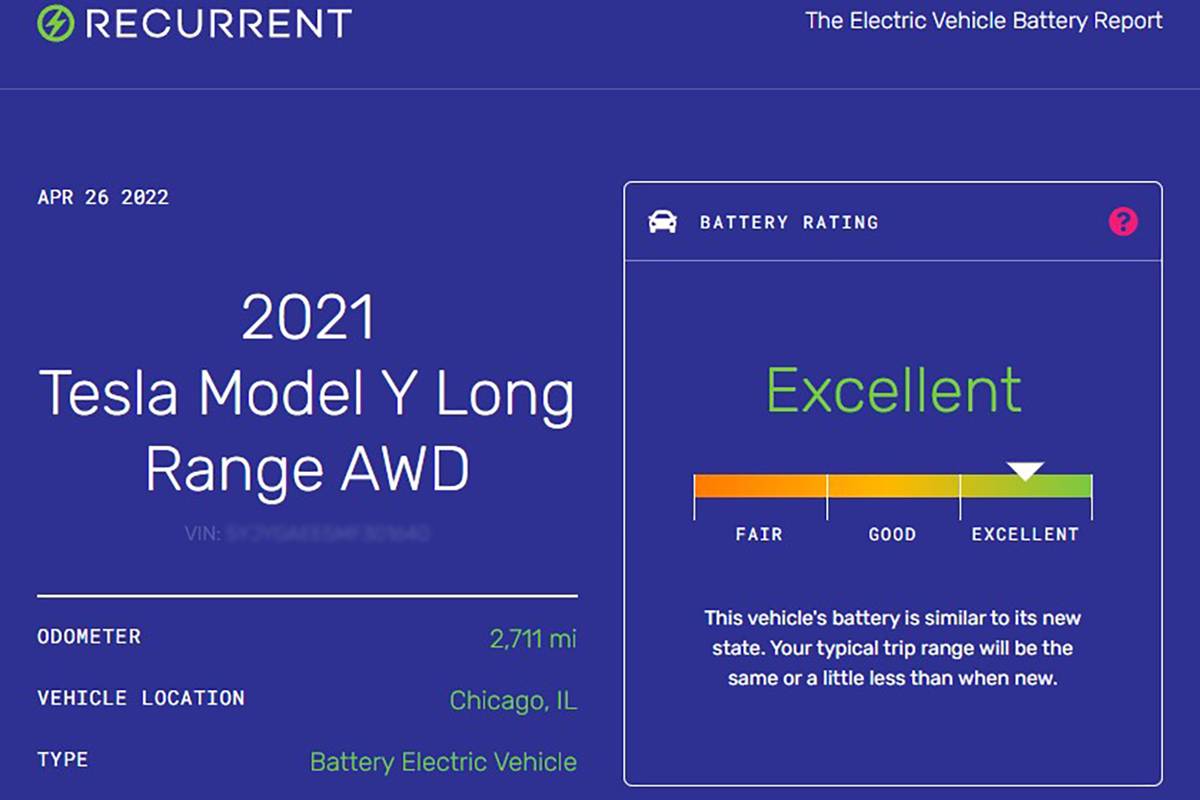

Recurrent also offers used-EV battery-condition reports, currently free, if you’re willing to take pictures of the prospective purchase’s displays and input them along with some other data. I gave it a try with Cars.com’s Model Y, and after signing up and entering the vehicle identification number, was instructed to charge the car fully, then photograph and input the odometer reading and projected range.

Within five minutes, I received the Model Y’s bill of health, which was Excellent, as expected. These reports aren’t at a point that they reflect exactly what the vehicle itself has experienced, as a conventional vehicle-history report might, but they do account for where the car has been and the battery capacity for its age and mileage compared with others of the same make and model, which the company says is enough for a reliable read of its health.

Naturally, the more EV owners who sign up to have their data sampled by Recurrent, the better the quality of the data and the greater the chance that someday you’ll be able to purchase a used EV with a more detailed record. Participants pay nothing and receive a monthly report that reveals their battery’s health, its maximum range, how that has changed with both time and weather variation, and also a prediction of its range in three years, providing the owner doesn’t move to a new region. This can help owners ensure that the vehicle will continue to meet their needs and perhaps determine when to sell it.

While these reports aren’t a guarantee, they seem like a better option than ruling out used EVs in the country’s warmer regions or avoiding the type altogether fearing battery problems.

Inspections Are Still Recommended

Just because EVs have fewer moving parts, require less maintenance, and have one big and expensive component that distracts attention and instills fear — the battery pack — it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t get a prospective purchase inspected by a qualified mechanic. Though it costs around $100 (depending on the shop and region), this step can save you more in the long run by ruling out stinkers, and it should give you an idea how much life is left on wear items like brakes and suspension components, even if they’re currently good enough. Naturally, it’s better to use a mechanic who’s trained to work on EVs, which may limit your choices and increase the inspection price; some otherwise-competent technicians might refuse to touch an EV.

Any mechanic should be able to determine if there are outstanding recalls on the vehicle, and that includes anything battery related. If you’re buying a Chevrolet Bolt EV or EUV of any age, for example, you should be getting (or will be eligible for) a battery pack from 2021 or later.

To this end, there’s no reason to fear an EV with a battery that’s been replaced due to recall, defect, age or damage apart from the usual expectation that a vehicle that’s been damaged significantly should cost less, even if it’s been repaired. This is one of the things an inspection can uncover.

Bear in mind that outside of recalls, battery replacement (specifically the cells or modules) may be the work of third parties, not the original manufacturer, as has been the case with hybrids. You’ll have to decide if you think aftermarket battery components are riskier than original equipment just as you would with other parts. Given the expensive labor involved and the insistence of some manufacturers to replace full packs rather than defective modules, it’s inevitable that third-party solutions will proliferate for high-volume EVs, especially those out of warranty.

Any seller claim of a battery replacement should be backed up with documentation and confirmed, where possible, by inspection.

More From Cars.com:

- Find EVs Near You

- More Electric Car News and Testing

- Electric Cars With the Longest Range

- Here Are the 11 Cheapest Electric Vehicles You Can Buy

Warranties Are in Flux

Many current EV powertrain warranties last at least eight years and 100,000 miles, and it’s now the norm for the coverage to transfer to subsequent owners, but that wasn’t always the case. Today’s warranties don’t apply to older models (unless the manufacturer’s terms have remained consistent, of course), so any shopper should verify the vehicle’s model year using a free VIN decoder and find the original warranty terms. (For your own protection — and ours — we have to leave to you the task of determining what coverage remains on a used EV you might be considering.)

Just to give you an idea of how much variance there is, even today’s new Tesla models provide 100,000, 120,000 or 150,000 miles of powertrain coverage, depending on the model and battery size. Originally, Tesla didn’t limit the miles at all. Another example of what you might encounter is the nontransferable powertrain warranties on older Hyundai EVs, such as an original Ioniq or Kona EV. That limitation was lifted with the 2020 model year for all Hyundai EVs.

As stated above, lithium-ion batteries lose capacity over time, but not all manufacturers’ warranties — past or current — have covered battery replacement should that capacity drop below a stated level. The capacity cutoff varies but has typically been 70%. Some warranties cover only failure or manufacturing defects, too.

Model-year 2016 is eight years ago as of this writing, so the vehicles on the market today that aren’t eligible for battery repair or replacement due to capacity loss potentially include the Fiat 500e, Ford Focus Electric, Mitsubishi i-MiEV, Smart ForTwo Electric and all 2016-or-older Teslas — and that’s if their warranties transfer and their odometers remain within coverage limits.

Free Charging and Some Features Might Not Transfer

Warranties aren’t the only things that might not transfer past the first buyer, at least not for free. Free DC fast charging (limited by kilowatt-hours or years), for example, typically starts and ends with the original buyer.

A so-called telematics connection to the car also isn’t guaranteed. Most EVs have been equipped with two-way data communication that let you use a smartphone app to start and stop charging, view range and precondition the cabin while it’s plugged into grid power to preserve battery charge for driving range. However, the connection might not be available or offered for free on a used EV. A fresh example: The Hyundai Ioniq 5 has just three years’ free Bluelink connectivity included at the time of purchase, which means the ability to precondition its cabin at whim while it’s connected to a charger will end at the end of that three-year period unless you’re willing to pay $99 per year. Though the key fob enables remote starting, it oddly works only when the car isn’t plugged in, meaning a smartphone and Bluelink subscription are required.

By contrast, Nissan seems to have gone out of its way to keep this kind of wireless connection (originally called CarWings on Cars.com’s 2011 Leaf) free, even for old models. Preconditioning is a hallmark of range preservation, especially for older vehicles that had less range to begin with, so Nissan makes sure connectivity doesn’t come at a price.

Also note that the wireless updatability pioneered by Tesla and adopted by many other automakers, especially in electric models, has an arguable downside: It allows manufacturers to shift toward subscriptions rather than one-time payment for features. Tesla has done so with Autopilot, to give one example, so owners keep on paying month after month. This opens the door for confusion at best and unscrupulous sales practices at worst. If you’re buying a used EV, and especially a Tesla, make sure you know what you’re getting for the purchase price — and what you’re not. The vehicle you test drive could behave very differently once money has changed hands.

Related Video:

Resale: The Market Giveth, But It Also Taketh

Buyers who are willing to ignore the hysteria over aging lithium-ion batteries and do a little homework are likely to find affordable used EVs, but if they decide to sell the car later on, they might discover that the same forces are still at play. In other words, you might decide that used EVs have value, but that doesn’t mean the market as a whole will. If your vehicle has gotten closer to — or passed — the end of its powertrain warranty, you might find its resale value has dropped precipitously. Likewise, if the manufacturer rolls out a new generation with longer range and more features, it might impact your model’s value more than the release of a new or refreshed model would for a used gas-powered vehicle.

An extreme example comes in the form of a cautionary tale. In 2022, rumors (and published reports) claimed that Chevrolet had discontinued production of the battery pack for the electric version of the Chevrolet Spark, which was sold from the 2014-16 model years in zero-emissions-vehicle states such as California. This would mean that Sparks with failing batteries would be little more than scrap and even healthy ones would likely lose value. GM denied those reports and blamed supply chain disruptions, but it raised the specter of an automaker choosing not to supply batteries or a shortage that could affect an owner who can’t wait for a repair. This would be more of a potential problem for low-volume vehicles like the Spark because there’s little enticement for an aftermarket company to take up the slack. We hope it never comes to that, though. Even if battery replacement doesn’t come into play until EVs are more than 10 years old or have traveled well over 100,000 miles, it needs to remain feasible or their environmental benefit will be in question, along with motorists’ comfort with used EVs.

Cars.com’s Editorial department is your source for automotive news and reviews. In line with Cars.com’s long-standing ethics policy, editors and reviewers don’t accept gifts or free trips from automakers. The Editorial department is independent of Cars.com’s advertising, sales and sponsored content departments.

Former Executive Editor Joe Wiesenfelder, a Cars.com launch veteran, led the car evaluation effort. He owns a 1984 Mercedes 300D and a 2002 Mazda Miata SE.

Featured stories